UN approves an updated cholera vaccine that could help fight a surge in cases

The World Health Organization has approved a version of a widely used cholera vaccine that could help address a surge in cases that has depleted the global vaccine stockpile and left poorer countries scrambling to contain epidemics.

WHO authorized the vaccine, made by EuBiologics, which also makes the formulation now used, last week. The new version, called Euvichol-S, is a simplified formula that uses fewer ingredients, is cheaper, and can be made more quickly than the old version.

The vaccine was shown to be help preventing the diarrheal disease in late stage research conducted in Nepal.

WHO’s approval means donor agencies like the vaccines alliance Gavi and UNICEF can now buy it for poorer countries. Leila Pakkala, director of UNICEF’s supply division, said in a statement that the agency will be able to boost supplies by more than 25%.

Gavi estimated there could be about 50 million doses for the global stockpile this year, compared with 38 million last year.

Dr. Derrick Sim of Gavi called WHO’s authorization “a lifeline for vulnerable communities around the world.”

More is still needed, however: Since January, 14 countries affected by cholera outbreaks have requested 79 million doses. In January, the U.N. agency said the global vaccine stockpile was “entirely depleted” until the beginning of March. As of this week, WHO said there were 2.3 million doses available.

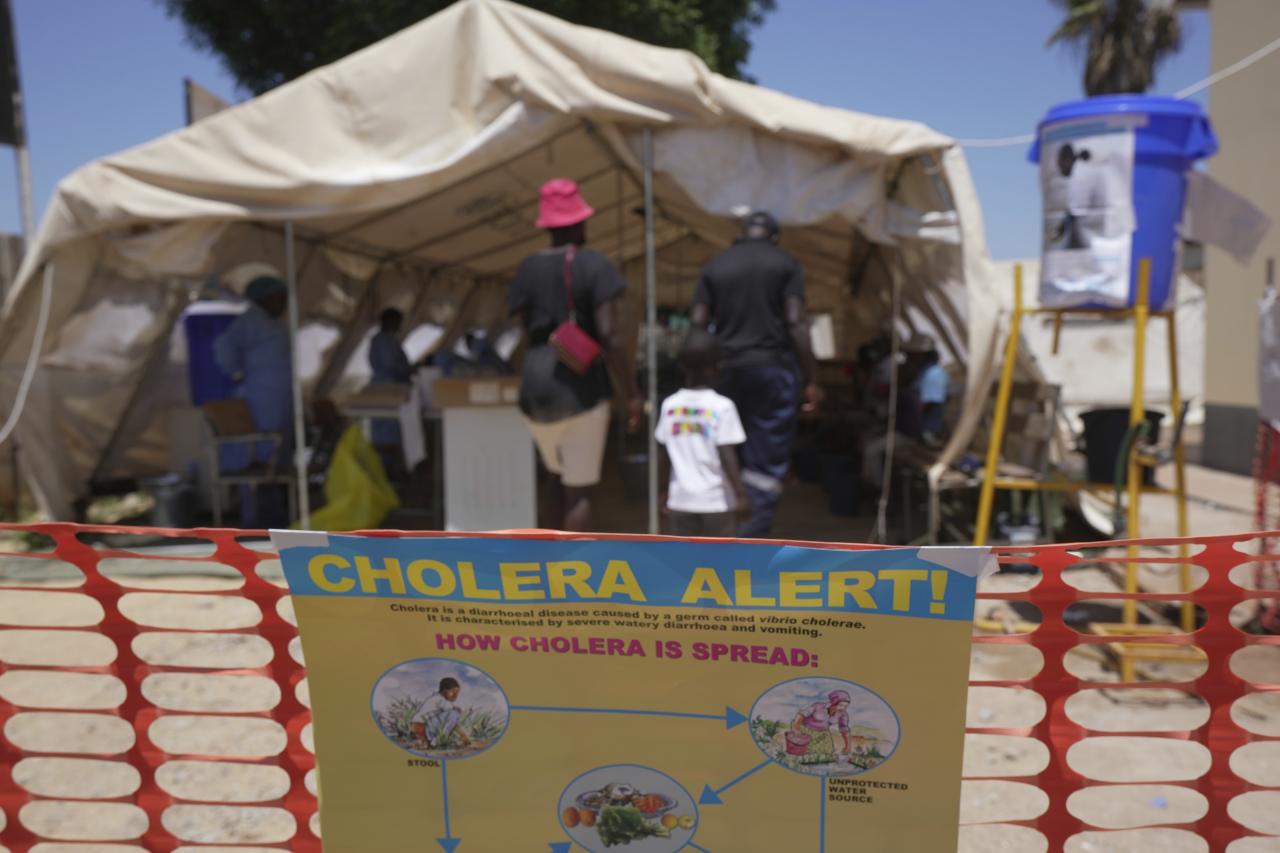

Cholera is an acute diarrhea disease caused by a bacteria typically spread via contaminated food or water. It is mostly seen in areas that have poor sanitation and lack access to clean water. While most people infected with cholera don’t experience symptoms, those with severe cases need quick treatment with intravenous fluids and antibiotics. If left untreated, cholera kills about a quarter to half of people infected.

Since last January, WHO has reported more than 824,000 cholera infections, including 5,900 deaths worldwide, with the highest numbers of cases reported in the Middle East and Africa. The U.N. agency said warming temperatures that allow the cholera bacteria to live longer, have also worsened outbreaks and led to the highest death rates in a decade.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.