Surprise finding sheds light on what causes Huntington’s disease, a devastating fatal brain disorder

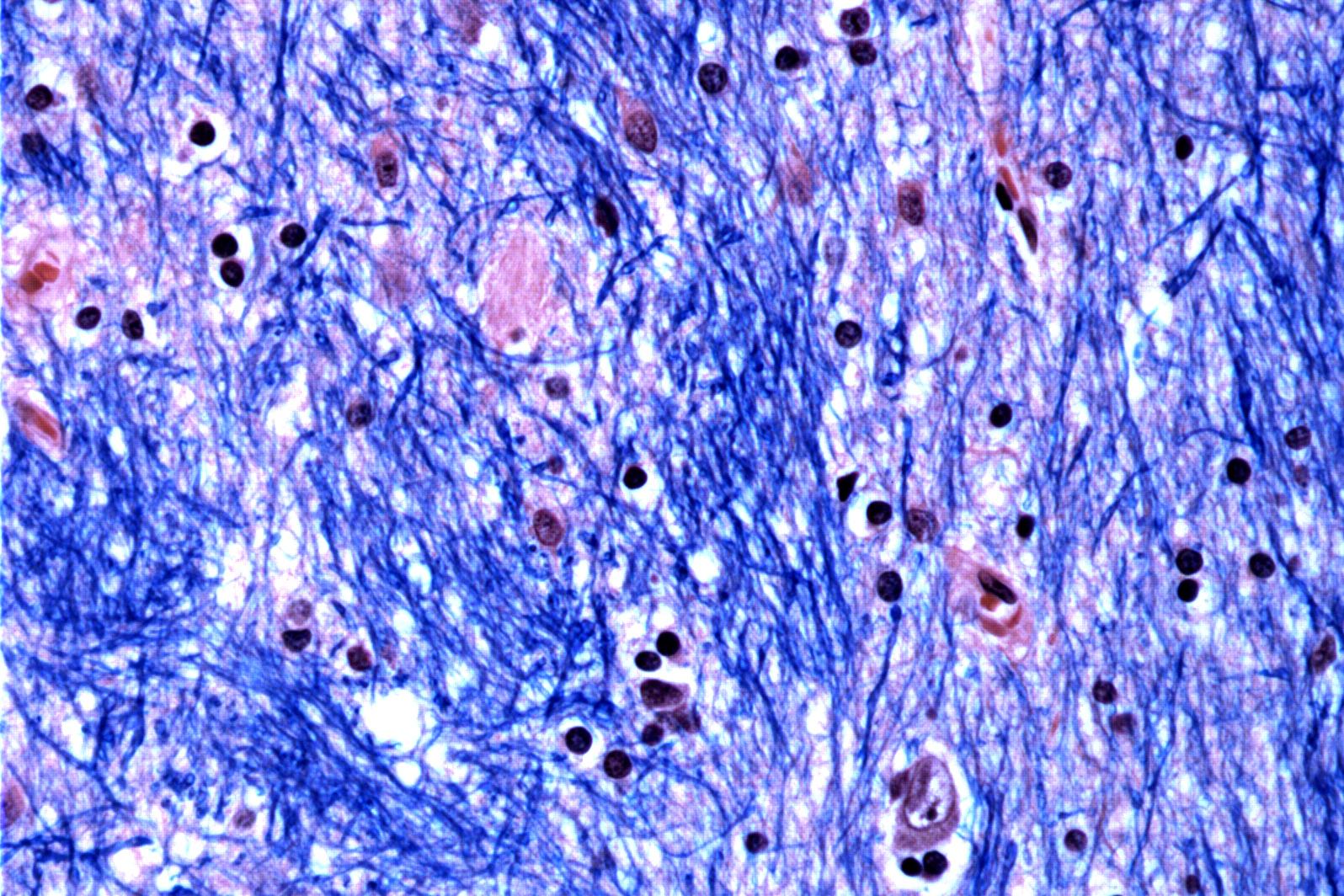

Scientists are unraveling the mystery of what triggers Huntington’s disease, a devastating and fatal hereditary disorder that strikes in the prime of life, causing nerve cells in parts of the brain to break down and die.

The genetic mutation linked to Huntington’s has long been known, but scientists haven’t understood how people could have the mutation from birth, but not develop any problems until later in life.

New research shows that the mutation is, surprisingly, harmless for decades. But it quietly grows into a larger mutation — until it eventually crosses a threshold, generates toxic proteins, and kills the cells it has expanded in.

“The conundrum in our field has been: Why do you have a genetic disorder that manifests later in life if the gene is present at conception?” said Dr. Mark Mehler, who directs the Institute for Brain Disorders and Neural Regeneration at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and was not involved in the research. He called the research a “landmark” study and said “it addresses a lot of the issues that have plagued the field for a long time.”

The brain cell death eventually leads to problems with movement, thinking and behavior. Huntington’s symptoms – which include involuntary movement, unsteady gait, personality changes and impaired judgment – typically begin between the ages of 30 and 50, gradually worsening over 10 to 25 years.

Scientists at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, McLean Hospital in Massachusetts and Harvard Medical School studied brain tissue donated by 53 people with Huntington’s and 50 without it, analyzing half a million cells.

They focused on the Huntington’s mutation, which involves a stretch of DNA in a particular gene where a three-letter sequence – CAG – is repeated at least 40 times. In people without the disease this sequence is repeated just 15 to 35 times. They discovered that DNA tracts with 40 or more such “repeats” expand over time until they are hundreds of CAGs long. Once CAGs reach a threshold of about 150, certain types of neurons sicken and die.

The findings “were really surprising, even to us,” said Steve McCarroll, a Broad member and co-senior author of the study, which was published Thursday in the journal Cell. The study was partly funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, an organization that also supports The Associated Press Health and Science department.

The research team estimated that repeat tracts grow slowly during the first two decades of life, then the rate accelerates dramatically when they reach about 80 CAGs.

“The longer the repeats, the earlier in life the onset will happen,” said neuroscience researcher Sabina Berretta, one of the study’s senior authors.

Researchers acknowledged that some scientists were initially skeptical when results were shared at conferences, since previous work found that repeat expansions in the range of 30 to 100 CAGs were necessary — but not sufficient — to cause Huntington’s. McCarroll agreed that 100 or fewer CAGs are not sufficient to trigger the disease, but said his study found that expansions with at least 150 CAGs are.

Researchers hope their findings can help scientists come up with ways to delay or prevent the incurable condition, which afflicts about 41,000 Americans and is now treated with medications to manage the symptoms.

Recently, experimental drugs designed to lower levels of the protein produced by the mutated Huntington’s gene have struggled in trials. The new findings suggest that’s because few cells have the toxic version of the protein at any given time.

Slowing or stopping the expansion of DNA repeats may be a better way to target the disease, researchers said.

Though there are no guarantees this would stave off Huntington’s, McCarroll said “many companies are starting or expanding programs to try to do this.”

——

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.