Incarcerated individuals with cognitive impairments encounter distinct obstacles. A particular institution is providing remedies.

In ALBION, Pennsylvania, the words “You are the Lighthouse in someone’s storm” are painted above a mural of a sailboat in the midst of ocean waves, surrounded by clouds against a blue sky. This message, though unusual for a prison wall, serves as a reminder of hope.

A vivid yellow Minion character on a deep blue door provides a list of instructions on how to greet fellow inmates in the segregated unit of Pennsylvania’s State Correctional Institution at Albion. Several rooms in the unit, known as “sensory rooms,” have a calming atmosphere with blue walls and subdued lighting.

According to experts, the special setting is a component of a program that strives to improve services for inmates with intellectual or developmental disabilities. This demographic is increasing and has posed a difficulty for corrections officials in finding a balance between security and necessary accommodations.

According to Steven Soliwoda, the creator of Albion’s Neurodevelopmental Residential Treatment Unit, incarcerated individuals frequently face difficulties in coping with excessive stimuli, rigidity, and following complicated instructions, causing them to exhibit intense behaviors that may result in additional punishment. Additionally, they may have challenges in understanding social norms, making them more susceptible to mistreatment, aggression, or exploitation while in prison.

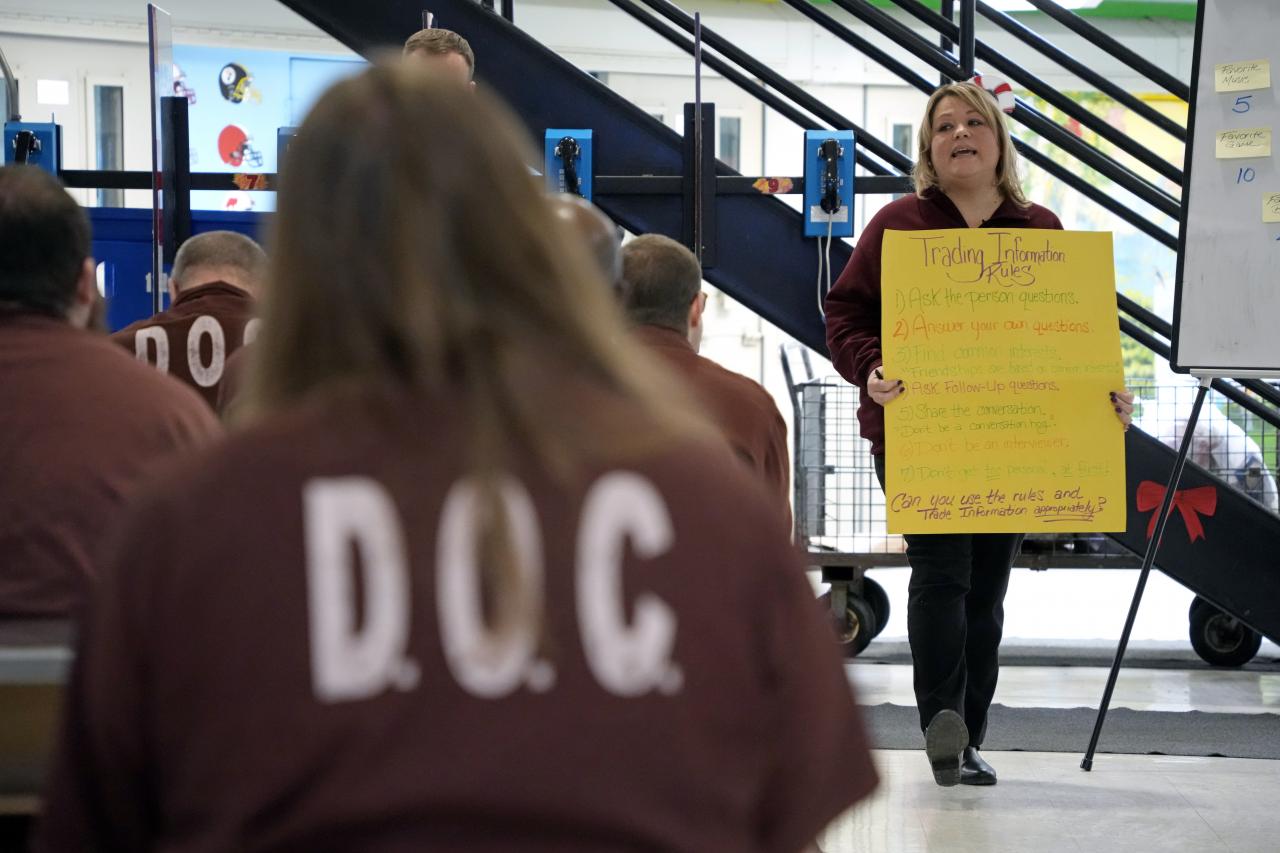

According to Soliwoda, who manages the program at Albion, individuals with autism and similar disabilities are often able to navigate their time in prison quietly. They may opt to isolate themselves or spend a lot of their time in their cell. However, the program gives them a platform to share their experiences and helps them develop the necessary independence and social skills to successfully integrate into society after their release.

It is difficult to determine the exact number of incarcerated individuals in the U.S. with autism or intellectual disabilities. However, recent research suggests that approximately 4% of inmates have autism and 25% have cognitive impairments, which is significantly higher than the rate in the general population. Some experts believe that the actual number may be even higher due to factors such as underdiagnosis prior to imprisonment and inadequate screening processes in correctional facilities.

The Neurodevelopmental Residential Treatment Unit, situated approximately 20 miles (32 kilometers) from Erie, Pennsylvania, was established three years ago and is the sole facility of its kind in the state. According to Soliwoda, the unit accommodates around 45 men, allowing staff to concentrate on personalized treatment and reducing sensory overload compared to prison settings.

There is a restricted exercise area that is not available to the inmates of the prison, where they are required to stay for medication and specialized treatment. They have access to puzzles, yoga mats, and drawing materials to assist in managing stressful situations. One prisoner spends a significant amount of time each day juggling in the communal space to help ease their mind – an activity that is typically not allowed in other units.

Christopher, a prisoner who has been diagnosed with autism, shared his initial reaction to the program by saying, “This feels like a form of therapy and rehabilitation for criminals, with all the paintings and positive messages surrounding it.”

Sean, an individual in confinement with a diagnosis of autism and cognitive impairments, shared that he feels secure in this environment. He explained, “Unlike in the general population, where I am more susceptible to bullying and other negative experiences, here I am able to learn coping mechanisms and emotional recognition.”

According to Soliwoda, his goal is to introduce more programming to the unit as it develops. However, officials from the corrections department currently have no intentions to implement this model in other prisons. Critics argue that this decision is flawed, as there are over 36,000 individuals in Pennsylvania state prisons who could potentially benefit from these services due to their disabilities.

Leigh Anne McKingsley, senior director at The Arc, a nonprofit organization serving individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, expressed concern that jails and prisons do not have adequate accommodations for various disabilities. She noted that this is especially true for prisoners facing these challenges.

McKingsley commented that those impairments appear to be overlooked.

Due to their lack of public visibility, it is difficult to determine what types of facilities prisons offer and how many have specialized units. The Arc has been actively gathering this information while providing training to various individuals, including law enforcement and prison employees, on how to better recognize and communicate with incarcerated individuals who have disabilities.

To maintain a safe environment and provide necessary accommodations, corrections officers at Albion are required to regularly attend training on de-escalation and crisis intervention. In cases where there is no specialized unit for developmental disabilities in Indiana, Nick Stellema, the state’s coordinator for the Americans with Disabilities Act, has aided corrections staff in effectively communicating with nonverbal autistic inmates.

Stellema and other supporters are cautious about separating incarcerated individuals with disabilities, as it goes against the purpose of the ADA to promote inclusion and integration, even in confinement.

He stated that individuals in the free world should interact with everyone, not just those with disabilities. He believes that having a deeper understanding of accommodations would benefit the entire system.

However, some proponents argue that isolating inmates with these impairments may be the most favorable course of action.

Brian Kelmar, president and founder of Decriminalize Developmental Disabilities, shared that a common issue they face is individuals behaving in a disruptive manner and consequently being isolated. He also stated that this experience has a more severe impact on them. Kelmar noted that after being in solitary confinement, their progress and social skills tend to regress, undoing any positive advancements they had previously made.

At Albion, employees utilize transitional cells as a measure for addressing specific behaviors. These cells are minimalistic in design and have safety measures in place, providing prisoners with a space to manage their emotions and focus on accomplishing objectives set by the psychiatric staff. Only once they have completed these goals are they permitted to return to the rest of the unit.

Colin, an inmate who has been diagnosed with autism and schizophrenia, stated that the prison staff allows individuals to take the necessary time for self-reflection and to calm down. This approach is seen as a means of promoting personal growth, rather than immediately issuing a punishment for any misconduct.

According to Randy Kulesza, a specialist in psychological services for the unit, the cells provide significant assistance to prisoners and do not jeopardize their eligibility for parole.

“I believe this method significantly reduces the number of instances of misconduct that these individuals have experienced. It allows us to address the problems early on and prevent them from escalating, while also giving these individuals hope for the future,” stated the speaker.