Autoimmune diseases, including lupus, affect a significantly higher number of women than men. Recent findings may provide insight into this disparity.

A recent study suggests that women are at a significantly higher risk than men for developing autoimmune disorders, in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own cells. This research may offer insight into the underlying reasons for this disparity.

According to a report by Stanford University researchers on Thursday, the focus is on how the body processes an additional X chromosome in females. This discovery may potentially result in improved methods for detecting and treating a range of difficult-to-diagnose and treat diseases.

University of Pennsylvania immunologist E. John Wherry, who was not involved in the study, stated that this shifts our understanding of the process of autoimmunity, particularly in regards to the gender bias between males and females.

According to various calculations, over 24 million individuals in the United States suffer from an autoimmune condition, with some estimates reaching up to 50 million. These disorders include lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and numerous others. It is worth noting that approximately 80% of patients are female, a phenomenon that has puzzled researchers for many years.

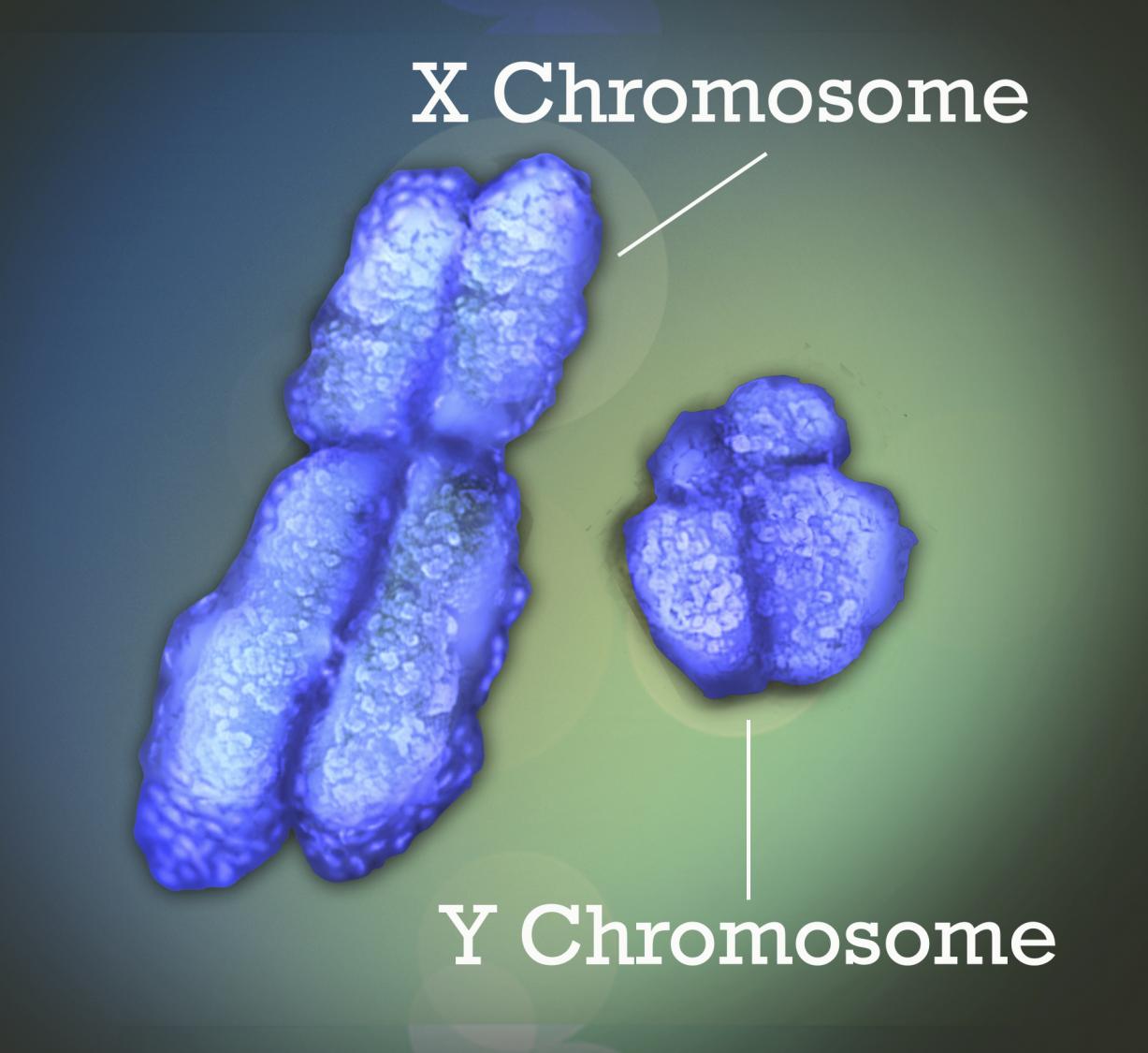

One hypothesis suggests that the X chromosome could be responsible. This is due to the fact that females possess two X chromosomes, while males have one X and one Y.

The latest study, published in Cell, reveals that an additional X plays a role – albeit in an unforeseen manner.

Each cell in our body contains 23 pairs of chromosomes, including the pair that determines our biological sex. The X chromosome contains hundreds of genes, while the Y chromosome in males is significantly smaller. In order to prevent the harmful effects of having too many X chromosome genes, female cells must deactivate one of their X chromosome copies.

Performing that so-called X-chromosome inactivation is a special type of RNA called Xist, pronounced like “exist.” This long stretch of RNA parks itself in spots along a cell’s extra X chromosome, attracts proteins that bind to it in weird clumps, and silences the chromosome.

Dr. Howard Chang, a dermatologist at Stanford, investigated the mechanism of Xist and his team discovered approximately 100 proteins that play a role in this process. Among these proteins, Chang recognized several that are linked to autoimmune disorders of the skin, where patients produce “autoantibodies” that incorrectly target these proteins.

“Upon further consideration, we pondered the following: These are the proteins that have been identified. But what about the remaining proteins within Xist?” Chang suggested. It is possible that this specific molecule, exclusive to females, could potentially arrange proteins in a manner that triggers the immune system.

If Xist is indeed accurate, it alone would not be able to result in autoimmune disease as all women would be impacted. For some time, researchers have believed that both a genetic predisposition and an external factor, like an infection or injury, are necessary for the immune system to malfunction. An instance of this is the connection between the Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis.

Chang’s group made the decision to genetically modify male laboratory mice to produce Xist artificially, without suppressing their sole X chromosome, and observe the resulting effects.

Scientists selectively bred mice that are prone to developing a lupus-like illness when exposed to a chemical irritant.

The research team concluded that the mice who created Xist also formed clumps of its distinctive protein and, when activated, experienced a similar level of lupus-like autoimmunity as females.

According to Chang, paid by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and supported by The Associated Press’ Health and Science Department, it is crucial for Xist RNA to exit the cell in order for the immune system to detect it. However, an environmental trigger is still necessary to initiate the process.

In addition to studying mice, scientists also analyzed blood samples from 100 individuals. They found autoantibodies that target Xist-associated proteins, which were not previously associated with autoimmune diseases. One possible explanation, according to Chang, is that traditional tests for autoimmunity were conducted using male cells.

Further research is required, but according to Penn’s Wherry, the results may provide a more efficient approach to diagnosing patients who exhibit varying clinical and immunological characteristics.

Autoantibodies to Protein A may be present in one individual, while another individual may have autoantibodies to Proteins C and D. However, understanding that all of these proteins are part of the larger Xist complex enables doctors to more effectively identify disease patterns, according to the expert. This discovery provides a significant piece of the puzzle in understanding the biological context.

Chang from Stanford ponders the potential for interrupting the process in the future.

“What is the process of RNA transforming into abnormal cells? This will be the next phase of the investigation.”

___

The AP Health and Science Department is backed by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely accountable for all material.