New research has shown promise in shrinking tumors in patients with aggressive brain cancer through a new attack strategy. The strategy has been successful in two initial trials.

A recent approach to combat a highly hostile form of brain cancer yielded encouraging results in two studies involving a small group of participants.

Researchers announced on Wednesday that they were successful in converting immune cells from patients into “living drugs” that were capable of identifying and targeting glioblastoma cells. In initial experiments, these cells were able to reduce the size of tumors, albeit temporarily.

Scientists have been utilizing a form of treatment known as CAR-T therapy in the battle against blood-based cancers, such as leukemia. However, they have faced challenges in adapting this approach for use against solid tumors. Two separate groups at Massachusetts General Hospital and the University of Pennsylvania are currently working on improved versions of CAR-T therapy that specifically target the defenses of glioblastoma.

Dr. Stephen Bagley of Penn, who was in charge of one of the studies, warned that it is still very early in the development process. However, he expressed hope that there is a promising starting point for future progress.

Glioblastoma, the brain cancer that killed President Joe Biden’s son Beau Biden and longtime Arizona Sen. John McCain, is fast-growing and hard to treat. Patients usually live 12 to 18 months after diagnosis. Despite decades of research, there are few options when it returns after surgery and radiation.

The immune system’s T cells fight disease but cancer has ways to hide. With CAR-T therapy, doctors genetically modify a patient’s own T cells so they can better find specific cancer cells. Still, solid tumors like glioblastoma offer an additional hurdle — they contain mixtures of cancer cells with different mutations. Targeting just one type allows the rest to keep growing.

Both Mass General and Penn created dual-sided methods and tested them on patients whose tumors resurfaced following customary treatment.

Dr. Marcela Maus’ research team at Mass General incorporated T-cell engaging antibody molecules into CAR-T therapy. This approach, known as CAR-TEAM, specifically targets the EGFR protein found in most glioblastomas while leaving normal brain tissue unharmed.

Penn’s method involved developing a “dual-target” CAR-T therapy that targets both the EGFR protein and a secondary protein commonly found in glioblastomas.

Both teams administered the procedure via a catheter into the cerebrospinal fluid surrounding the brain.

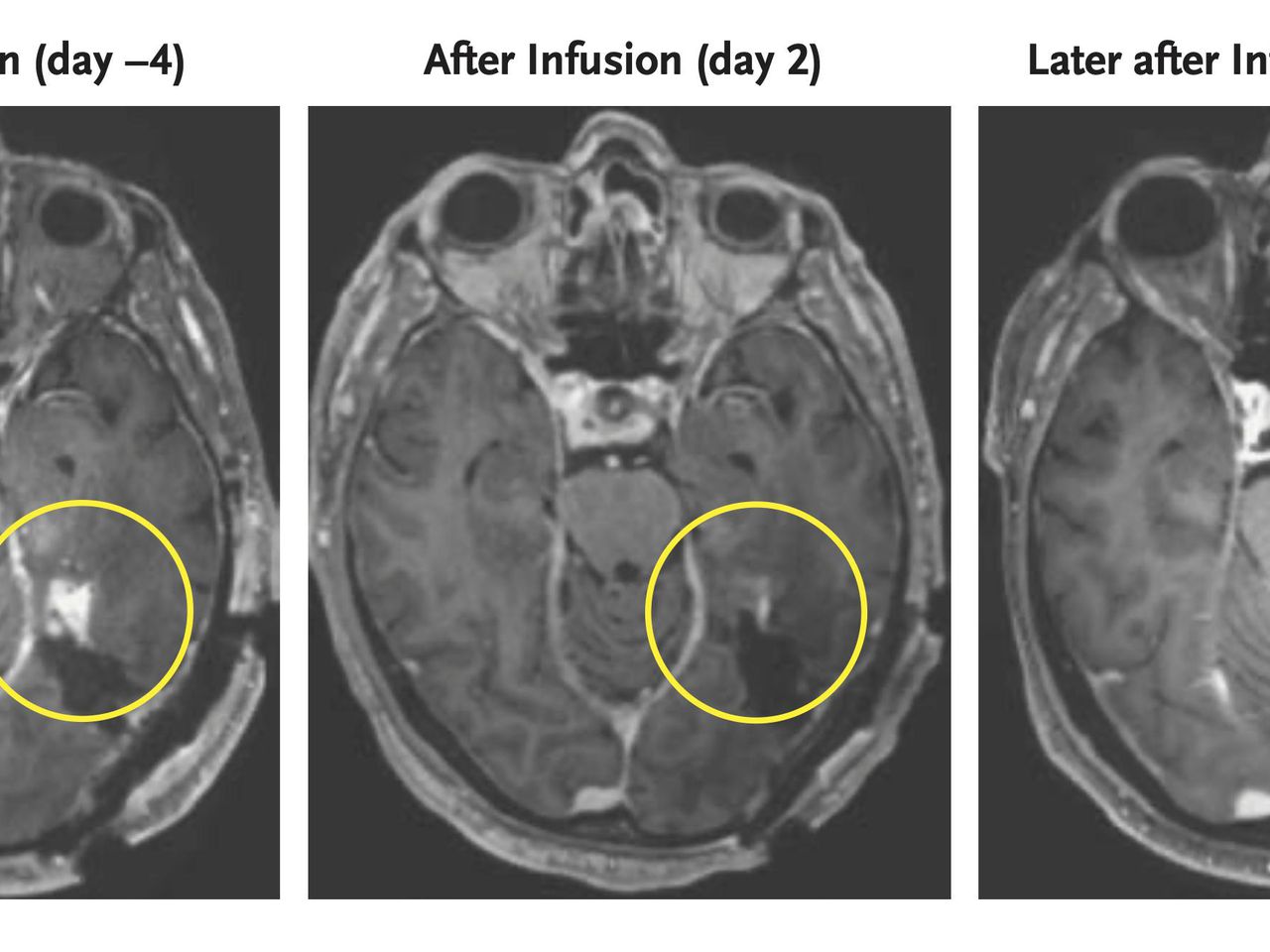

According to a report in the New England Journal of Medicine, Mass General utilized their CAR-TEAM to assess three patients, and subsequent brain scans a day or two later revealed significant shrinkage of their tumors.

Maus expressed disbelief and stated, “It’s hard to believe. That’s not something that typically occurs.”

Soon after, two of the patients experienced tumor regrowth. Despite administering a repeat dose to one of them, the treatment was unsuccessful. However, one patient showed a sustained response to the experimental therapy for over six months.

Similarly, Penn researchers reported in Nature Medicine that the first six patients given its therapy experienced varying degrees of tumor shrinkage. While some rapidly relapsed, Bagley said one treated in August so far hasn’t seen regrowth.

Both teams are faced with the task of prolonging its duration.

Bagley stated that if it is not long-lasting, none of this will be significant.

___

The AP Health and Science Department is backed by the Science and Educational Media Group of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The AP holds full responsibility for all of its content.

Source: wral.com